- Home

- Patricia MacLachlan

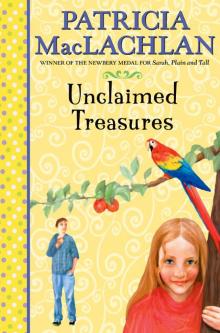

Unclaimed Treasures

Unclaimed Treasures Read online

Dedication

For three Unclaimed Treasures, with love.

Craig, Nancy, and Varnetta Arlene

Contents

Dedication

Prologue

1: The Beginning

2

3

4

5

6: The Middle

7

8

9

10

11: The End

12

13

14

15

About the Author

Back Ads

Other Books by Patricia MacLachlan

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

“I found it!” The tall man stood in the doorway, grinning, holding up the painting for her to see. “In the attic.”

“Ah.” The woman turned from the window, slowly, carefully. She was very large. Soon she would have a baby. “The apple tree.” Her voice was like a sigh. “Just look at the color of the blooms.”

The man and woman smiled at each other over the painting.

“And it’s still there, that old tree,” said the man. He moved to the window to look out over the wide sweep of lawn. He walked with a limp. “Still dying, is it?”

“It was always dying,” she said. “You remember. We were always told not to climb it. Warned and shouted at and chased when we did.”

The man nodded. “But we had to climb it,” he said. “They should have known we had to climb it. Just because it was forbidden.”

“It was like a short story, that summer,” said the woman, settling in the wing chair by the window. “A short story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.”

The man smiled and sat on the arm of her chair.

“Once upon a summer,” he began, “there was a tree full of blooms that would soon become fruit, and a pair of twins, a boy and a girl. And the girl wished to do something important and extraordinary.”

1

The Beginning

It was a summer that began and nearly ended with a death. One of the next-door aunts died the first week that Willa and Nicholas moved to their new house. The air was still and balmy, and they hung out the upstairs window watching the relatives and friends parade in and out of the gray Victorian house next door.

“It looks like a parade of ants,” said Nicholas, hanging way too far out the window. “Aunts, ants. Get it?”

“Yes,” said Willa, hanging on to his pants and watching for her true love.

Willa was always watching for her true love, in every line outside the movie theater or ice rink or at the bank. Stopped at a light, Willa always looked over to the next car for him. He would, she knew, be tall and solemn. Solemn. Not like her mother, who was loud and cheerful and wore bright colors. Not like her father, who murmured a lot and rustled his class papers. Willa loved her mother, though she did not understand her. Willa loved her father, too. He was the one who came up at night and nuzzled in Willa’s neck and sang songs she knew he made up. They droned some like a hive of bees and put her to sleep. Willa had read in a book once that she might fall in love with her father. So she tried—but she couldn’t. She threw herself into his arms once, pressing up close against him, whispering in his ear the way it was done in the movies. He had looked at her strangely, smiling, as if he had read the same book or seen the same movies.

“Great Hoover Dam,” said Nicholas in the window. “Will you look at all the long black cars.”

Willa smiled. Nicholas was experimenting with bad language, slightly disguised. She squeezed next to Nicky and leaned farther out. Maybe her true love would be an undertaker. The undertakers were dressed in black, and they wore gloves and looked solemn. All except the one who was earnestly picking his nose. None was her true love.

As Willa and Nicholas watched, a door to the side porch next door opened, and a boy came out to sit on the step. He began eating an apple, neatly spitting out the peel as he ate. He looked up and saw them in the window.

“Hi,” he called. His hair was fair and hadn’t been brushed.

“You’re spitting out the healthiest part of the apple,” Willa called.

The boy nodded, smiling slightly.

“I’m sorry someone died there,” said Nicholas kindly.

Willa was horrified. Things like death and pimples and mayonnaise in the corner of someone’s mouth were best left unmentioned, she thought.

The boy was not horrified, however.

“It’s an aunt,” he called up. “A great-aunt. One of the Unclaimed Treasures.”

“Unclaimed Treasures?” asked Willa.

“One of the aunts,” he said. “Unmarried. Unclaimed. There are two left over,” he added. He spit a large piece of apple peel into the bushes. “Why don’t you come visit?”

Nicky and Willa looked at each other. Go over next door? Where there was a funeral? For someone they didn’t know?

“I’ve never been to a funeral,” whispered Nicky. It was clear he wished to go.

Willa stood up, her face pale.

“But there’s a dead aunt over there,” she whispered. Nicholas took her hand.

“Death,” he announced, “is not catching, Willa.”

And that was the beginning.

The boy’s name, it turned out, was an unfortunate one—Horace Morris—though it did not trouble him. He announced it matter-of-factly, calmly, like a weatherman announcing rain.

“I’m Willa Pinkerton,” said Willa. “And this is my younger brother, Nicholas.” Seven minutes younger Nicky was, since they were twins. But Willa always introduced him as her younger brother. And Nicky, being Nicky, never cared.

“Come on.” Horace Morris beckoned them. “There’s good food inside.” It was obvious Horace Morris liked food. His pants bulged at the pockets, and he had a slight roll over his belt.

Inside, the kitchen had large black and white floor tiles, splendid for hopscotch, Willa thought, and high ceilings and lots of food and people. Everyone there was smiling and talking, including Horace’s two aunts—the leftover Unclaimed Treasures. They did not look like any aunts Willa and Nicholas had ever seen before. Though they were great-aunts, ancient and wrinkled, they were dressed in bright colors, and they were drinking and smoking. Aunt Lulu was teetering on lavender high-heeled shoes with many straps that crisscrossed and crept up her legs, ending somewhere under her dress.

“How nice for Horace to have you here!” she exclaimed. “You may try the wine.”

The plump one was Aunt Crystal.

“Welcome to the neighborhood,” she said. “The former owners of your house did not treat our cats with respect.”

Willa noticed that there were two cats on the counter attacking a roasted turkey.

“We have three cats,” Aunt Crystal confided. “The two on the counter are named Black and Blue because they fight. Gloria is in the parlor keeping company with Mab.”

“Is Mab another cat?” asked Nicky politely.

“Oh no, dear,” said Aunt Crystal, smiling and patting his hand. “Mab is the deceased.”

Horace handed Willa and Nicholas glasses of wine, and Willa’s stomach began to feel uneasy as they moved through the mass of people in the dining room and into the parlor.

“Holy Crisp,” murmured Nicky, for he had just spied the open coffin sitting in the bay window.

“Come on in,” invited Horace. “If you want you may have a look.”

Willa gulped at her wine, and they moved closer. Gloria, a long-haired Persian, was indeed keeping company with Aunt Mab. She was perched just above Aunt Mab’s folded hands, preening herself. Aunt Mab was laid out in what was really the music room, right next to the Kn

abe. She had a mildly sour look on her face, as if she had expected someone to play Schubert or Chopin, but had been presented with Czerny exercises instead.

Willa drained her wineglass nervously and sat on a velvet chair. She had never in her life drunk wine. But she remembered her mother once, after a party, dressed in an India print dress and in bare feet, standing in the kitchen singing three verses of “Bringing in the Sheaves.” Her mother had sung it “Bringing in the Sheets,” and her father had made coffee and been amused. Willa beckoned to Nicky.

“Do I look or sound funny?” she whispered.

Nicky shook his head, then stared again at the coffin.

“Very well, then,” Willa said brightly. “I’ll have another.”

Horace Morris brought her another wine and sat down on a stool.

“Where are your mother and father?” Willa asked him.

“My father is over there,” he pointed. “See? The tall one next to Aunt Crystal.”

Willa looked, but all she could see were people milling about.

“My mother is not here for a while,” Horace went on. “She’s gone to seek her fortune.” Horace was eating another apple, carefully spitting the peels into a potted plant.

“Seek her fortune?” asked Nicky. Willa knew he had visions of a pig or a dog with a long stick and a kerchief over its shoulder. Nicky was a great reader.

Horace nodded and spit. “She said the Treasures take care of the house and of me. She’s out in the world looking for something that needs her.”

“That’s wonderful,” said Willa, staring at Horace. “I wish my mother would do that.”

“Our mother is having a new baby,” explained Nicky.

Horace was impressed. “She is?” He looked at Willa. “I wish my mother would do that,” he said fervently.

Willa had a sudden and sharp memory of a day last week, just before dinner, talking about the new baby.

“Will it be twins, like us?” Nicky had asked.

Their mother, huge and brightly colored like an air balloon, turned sideways at the kitchen counter to cut tomatoes. She shook her head.

“One heartbeat, the doctor says.”

“That’s what he said before we were born!” protested Willa, dismayed at the thought of two babies. One was bad enough, smelling and crying and dirtying up the house.

“That was eleven years ago,” said their mother. “They know more now.”

Willa sipped her wine, thoughtfully. They didn’t know enough, she thought, to keep her mother from being pregnant. Her mother should be out in the world doing something important and extraordinary. Like Horace Morris’s mother. That’s what I will do someday, Willa thought. I know it. Something important and extraordinary. Not like having babies. You just popped babies out and had them on your hands for years.

“Something important and extraordinary,” Willa said out loud. “That’s what I am going to do. Someday.”

“Do the two go together?”

Willa and Nicholas looked up.

“Papa,” said Horace. “This is Willa and Nicky. From next door.”

The tall man smiled and pulled up a chair to sit.

“I heard about you. From the Treasures,” he said.

Willa stared at him. He had a sweet, sad smile, something like Horace’s.

“We’re sorry about”—Nicky bent his head in the direction of the coffin—“her being . . .”

“Dead,” said Horace’s father kindly. “Thank you.” He looked at Willa again, studying her. “Well, do they? Go together? Things important and things extraordinary?”

Willa swallowed.

“Do you mean,” said Horace’s father, “going-skydiving important and extraordinary or saving-a-life important and extraordinary or creating-something-beautiful important and extraordinary?” He smiled. “Or just plain everyday important and extraordinary?”

Willa blinked. There was a silence.

“She’s drunk, I think,” announced Nicky, who had never seen his sister so silent.

Horace’s father laughed.

“Have a sandwich, Willa.” He turned to Horace. “We’ll have to leave for the church soon.” He reached out to touch Horace’s wild hair, and Willa saw that he had a smudge of blue paint on his wrist. He stood up, looking tall and solemn.

“Come back often,” he said to Willa and Nicholas. He went over to the coffin, slowly and gracefully plucking up the cat from inside.

“We’d better go,” Nicky whispered to Willa. She nodded.

“Tomorrow,” Nicky said to Horace. “We’ll see you tomorrow.”

He pushed Willa in front of him, through the dining room and into the kitchen. Aunt Crystal was sitting up on the counter, her legs dangling, either Black or Blue batting at the beads around her neck. She waved. Aunt Lulu, cigarette ashes sifting down the front of her dress, opened the door.

“Thank you for coming,” she trilled after them. “I’m sure you were a comfort.”

Outside it was quiet, still again, as if they had passed from one world back into another. Everything had blurred edges, the apple tree, their mother’s phlox, even Nicky walking beside her. Willa knew it was the wine. They looked at each other, and Nicky began to laugh.

“What?” asked Willa.

He pointed to her hand. She still carried her wineglass.

They walked into the kitchen, where their father was making spaghetti sauce, stirring and sniffing and making embarrassing sounds of delight. Their mother was sitting at the table, chopping celery.

“Where have you two been?” she asked them. “Supper’s almost ready.”

“We have been attending a funeral next door,” said Nicky very formally. This caused Willa and Nicky to burst into laughter, and they sat down at the kitchen table, Nicholas snorting into his hand, and Willa whooping. Their mother and father smiled at them and at the wineglass.

Finally Nicholas caught his breath.

“They have Horace Morris over there,” he said, wide-eyed. “And Unclaimed Treasures and cats.”

And my true love, thought Willa, taking the knife from her mother to help chop celery for salad. Tall and solemn, just as I knew he’d be.

2

A gray morning mist hung over the garden and yard, and Willa busied herself with kissing her bedpost. She had drawn lips there long ago, when she was nearly seven and when she and Nicholas had first learned about love and sex and flutterings. It had been right after their LST, as Nicky called it. LST for Little Sex Talk. Nicky had been fascinated and had asked their parents for the most specific details, while Willa had been disinterested in all but the kissing. Kissing, along with what Willa called “long and meaningful looks” and Nicky resolutely called “eyeballing.”

“But how did you first know Daddy liked you?” Willa asked her mother.

Her mother smiled. “I could feel him staring at me. I knew he was interested.”

“You mean a long and meaningful look?” asked Willa enviously.

“Eyeballing,” said Nicky. “He was eyeballing her.”

“Nicholas,” said their father, smiling slightly, “there must be a better way to express it.”

“A long and meaningful look,” said Willa, nodding her head.

“Eyeballing,” said Nicky softly.

Their father stood up and went to the kitchen to make a drink, a certain signal that the talk was over.

“It was something in-between,” said Willa’s mother after a moment, her voice startling them with its softness. She stared at a spot over Willa and Nicholas’s head. “Something very lovely and in-between.”

Her mother’s strange look made Willa restless. Uncomfortable. And the realization that her own mother and father had some acquaintance with love and sex and flutterings made her nearly mute. Until then, Willa had thought it all reserved for young people in red cars with racing stripes, or those with picnic baskets.

Even now the thought was troubling, and when thoughts troubled Willa she wrote them on small slips of p

aper and hid them in her bureau drawers for later. Somewhere, underneath her clothes, along with a pack of bubble gum, there was a small slip of paper that read: June 7, I know how it is done.

And now that Willa was nearly twelve, on the edge of the world of racing stripes and picnic baskets and her true love, she had taken to practicing bedpost kissing with more verve. Sometimes Nicholas watched.

“Does it feel queer and exciting yet?” he asked. On his lap lay a recent magazine open to an article that described for those who cared to know it the feelings accompanying kissing.

“Osculation,” mused Nicky. “Another name for kissing.” He looked up. “Well, is it? Queer and exciting?”

Willa unclamped her lips for a breath. “No,” she admitted. “But this is only early practice.”

“I think,” observed Nicky, “that kissing a mahogany post may be a hindrance.”

Willa pushed her lips against the post again, and closed her eyes. She unclamped and looked at Nicky.

“You’re right,” she said. “I need another human pair of lips.” She stared at Nicky.

“Oh no! Not mine!” protested Nicky.

“All right,” said Willa. “Not yours.”

Nicky peered closely at Willa.

“And not his either,” he added pointedly. “He’s married.”

“Whose? What?” Willa jumped self-consciously.

Nicky picked up his sketch pad and sat cross-legged on Willa’s floor.

“You know that I know who you’re thinking about,” said Nicky. He sketched in long strokes.

“Who?” shrieked Willa, furious. “Who?”

Nicky stopped sketching and turned to look out the window, past the old apple tree, at the house next door.

Willa shrugged. “I just thought he was nice.”

“No sir, you didn’t just think he was nice,” he mimicked her. “You were tongue-tied.”

“It was the wine,” said Willa fiercely. “And the funeral. My first, after all.” She began to erase the lips on her bedpost and draw new, larger ones.

Nicky sighed. “All right. A bet, then.” He held his drawing out and looked at it. He rubbed a part of the drawing with a finger. “I will bet all my chores for the week that you think he is your true love. I know just how you look when you think you have found your true love.”

More Perfect Than the Moon

More Perfect Than the Moon Fly Away

Fly Away Unclaimed Treasures

Unclaimed Treasures The Facts and Fictions of Minna Pratt

The Facts and Fictions of Minna Pratt The Poet's Dog

The Poet's Dog Journey

Journey White Fur Flying

White Fur Flying The True Gift: A Christmas Story

The True Gift: A Christmas Story Sarah, Plain and Tall

Sarah, Plain and Tall Word After Word After Word

Word After Word After Word Seven Kisses in a Row

Seven Kisses in a Row Edward's Eyes

Edward's Eyes Caleb's Story

Caleb's Story Dream Within a Dream

Dream Within a Dream The Truth of Me

The Truth of Me Wondrous Rex

Wondrous Rex Baby

Baby A Secret Shared

A Secret Shared Grandfather's Dance

Grandfather's Dance Cassie Binegar

Cassie Binegar Waiting for the Magic

Waiting for the Magic The Boxcar Children Beginning

The Boxcar Children Beginning My Father's Words

My Father's Words The True Gift

The True Gift